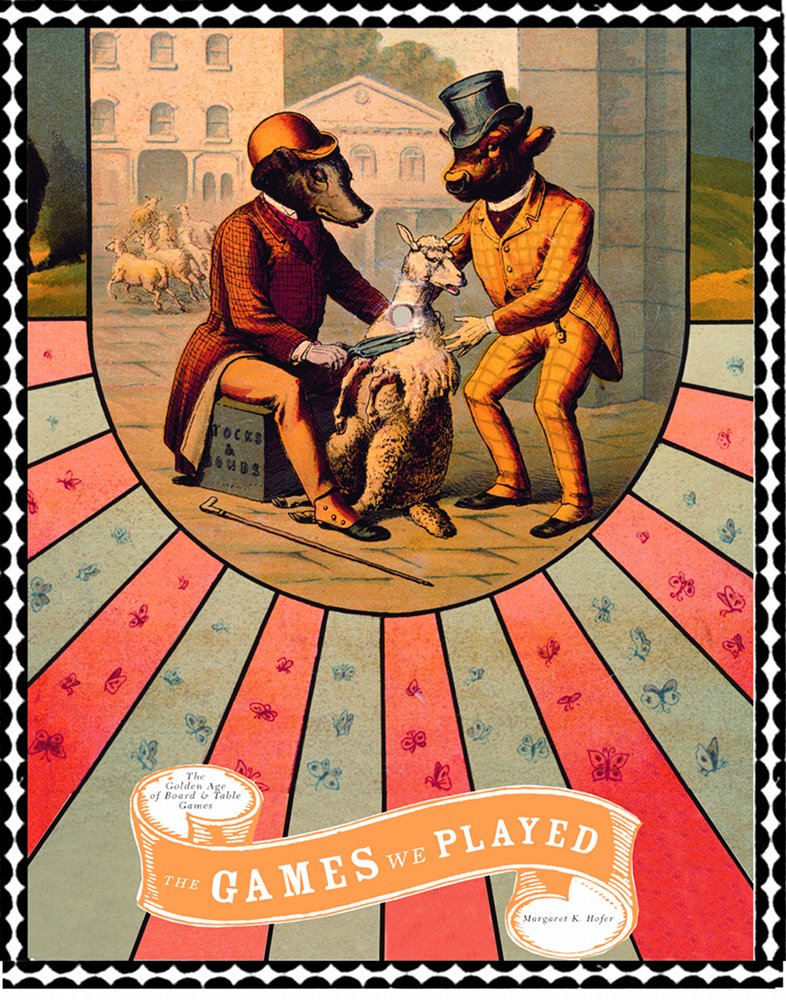

The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board & Table Games

Aside from a two page foreword by Kenneth T. Jackson, there is little in the way of lengthy text in Margaret K. Hofer’s The Games We Played, other than in her introduction which covers the economic and social factors that led to the Golden Age of board games in the 1880s as well as each chapter introduction. This is not a bad thing. Instead, the reader gets 159 pages of rich illustrations of games like Rival Policemen, Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York, and Peter, Peter, Pumpkin Eater. Published in 2003 by Princeton Architectural Press, The Games We Played uses the New-York Historical Society’s Liman Collection of games as its basis and indeed resembles a large museum exhibit catalogue. As such, it makes for a great coffee table book, but it would also be a valuable addition to a classroom or school library for a glimpse back into the Gilded Age of America as well as the early Progressive Era with games celebrating American victories in the Spanish-American War.

Aside from a two page foreword by Kenneth T. Jackson, there is little in the way of lengthy text in Margaret K. Hofer’s The Games We Played, other than in her introduction which covers the economic and social factors that led to the Golden Age of board games in the 1880s as well as each chapter introduction. This is not a bad thing. Instead, the reader gets 159 pages of rich illustrations of games like Rival Policemen, Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York, and Peter, Peter, Pumpkin Eater. Published in 2003 by Princeton Architectural Press, The Games We Played uses the New-York Historical Society’s Liman Collection of games as its basis and indeed resembles a large museum exhibit catalogue. As such, it makes for a great coffee table book, but it would also be a valuable addition to a classroom or school library for a glimpse back into the Gilded Age of America as well as the early Progressive Era with games celebrating American victories in the Spanish-American War.

While Hofer links the 1887 game The World’s Educator to Trivial Pursuit and Monopolist from 1885 to Parker Brothers’ Monopoly, The Games We Played is refreshingly devoid of many other references to “classic” games that most modern board game enthusiasts consider stale or dead. Looking at the Monopolist board or The Checkered Game of Life (1866), it is hard to envision their latter-day descendants. Even Anagrams from Milton Bradley in 1910 does not bear much resemblance to Scrabble, aside from letter blocks. The only game I recognized was Tiddledly Winks, which I played in the 1980s as a child. From Hofer I now know that the game was patented in England in 1889 with the New York-based McLoughlin Brothers patenting Improved Game of Tiddledy Winks in 1890. Parker Brothers had a version copyrighted in 1897 as The Popular Game of Tiddledy Winks.

The McLoughlin Brothers company dominates The Games We Played, just as they “dominated the industry with sumptuous eye-catching packaging that was frequently more compelling than the games it contained” in the period between 1858 to 1920 according to Hofer. Milton Bradley went on to purchase the company in 1920. This may also explain why McLoughlin Brothers games are so unfamiliar and seem so novel, as Parker Brothers probably did not continue to produce their older titles. I say probably because readers interested in a detailed account of the Golden Age of board games will be disappointed by Hofer’s lack of a historical narrative with any detailed information on the game manufacturers or designers themselves or their economic battles with each other. For that we do have David Parlett’s The Oxford History of Board Games, which Hofer used in her research.

Hofer’s chapter introductions though do make connections between the board game offerings of the era and the changing social and moral values in America of the time period. Her chapter “Morals to Materialism” ties board games like The New Pilgrim’s Progress (1893) and Game of the District Messenger Boy, or Merit Rewarded (1886) to the nascent idea of the American Dream and self-made men. Hofer sums up the game Cash: Honesty is the Best Policy: “Cash provided those who could afford the simple $1.50 game with the opportunity to climb the ladder from errand boy to millionaire.” As such, games like Cash were echoes of Horatio Alger Jr.’s series of popular “rags to riches” stories prevalent at the time, emphasizing hard work and clean living as the paths to success. On the other hand, of course, many of these games were just plain materialistic and about wish fulfillment, such as the early 1850 game Yankeee Pedlar, or What Do You Buy? from John McLoughlin before starting McLoughlin Brothers. Is Yankee Pedlar really so different than a Barbie game about shopping at a mall? Hofer’s sixth chapter,”The Urban Experience”, details board games specifically about New York, prosperity, and navigating one’s way in increasingly complex cities. To Hofer, “these games betray the sense of dislocation felt by Americans experiencing rapid urban growth and suggest their collective aspirations for worldly urban sophistication.”

Though the games are presented in the first chapter, “Parlor Amusements”, I think the McLoughlin Brothers games of The Pretty Village in 1890 and 1897’s The New Pretty Village also reflect the materialistic longing of the later chapters, as well as dreams for success. With my fondness for miniature buildings, how could I not be fascinated by the Pretty Village series? Essentially the “games” were packs of card buildings that could be assembled for play. Hofer identifies that the “quaint stuctures in this popular game reflect a new nostalgia for a simple, agrarian past.” I imagine though that the designers chose the village for more practical reasons. Modeling skyscrapers and other “modern” marvels to the scale of cut-out figures or toy soldiers would have been impractical. The boy in the illustration in his cowboy outfit is able to join his younger sister’s genteel play probably because he will have a small army of cowboys and Indians to raid her peaceful village. It is charming to see the forerunners of World Works Games and other paper terrain efforts as early as the 1890s.

War Games

The other particularly captivating section of The Games We Played for me was Hofer’s exceedingly brief fourth chapter, “War Games”. Historical war gamers will find the tiny chapter interesting as it has games covering Napoleon through to the Spanish-American War. Napoleon: The Little Corporal from Parkers Brothers in 1895 traces Napoleon’s life. What fan of Napoleonics doesn’t love the Battle of Wagram in 1809 or the 1805 Campaign at Ulm? This is a board game though, closer to The Game of LIfe than any tactical war game, This is the case for all the games featured in the “War Games” section, though the playing map for Game of War at Sea or “Don’t Give up the Ship” looks promising for chit-based war games. Players must battle in the Atlantic and Carribean for dominance in this Spanish-American war title from 1898. I can’t help thinking though that there is some possibility for Civil War, Mexican-American War, or even earlier conflicts on its playing surface, which features a checkerboard gridded sea and American and Canadian cities. The playing board’s map goes as far west as Austin, Topeka, and Sioux City.Uncle Sam at War with Spain was also released in 1898, the same year of the Spanish-American War. These Golden Age board games were very topical as patriotism soared. The subjects also seemed to be mostly real and historical. Roosevelt at San Juan and Schley at Santiago Bay were two other titles, this time released in 1899 from Chaffee & Selchow. Schley’s name should be famous to students of American naval history for the Sampson-Schley controversy. At the time of the game’s printing though, Winfield Scott Schley was an accomplished naval hero.

There are a few exceptions to the historical battles and figures covered such as the generic Mimic War which contained 30 paper stand-up soldiers, which Hofer explains were for children “to act out their favorite war battles”. “Advance and Retreat also seems to be a non-specific game of battle. Earlier in the book, Hofer includes Chivalry from Parker Brothers in 1888, which “had complex rules and demanded strategic skill to win”. Unfortunately one of Hofer’s other notes is frustratingly not illustrated by her choice of images; she captions the innocuous cover for Game of The Little Volunteer with the note that, “Grisly images showing bloodshed were apparently not troubling to children and parents of the 1890s.” On the game’s cover, a child beats a drum, a cute dog stands with a rifle in paw and a party hat on its head, and there is a mounted cavalry officer with his sword at his side diagonally opposite the angelic pair. I would like to see the “grisly” depictions to which Hofer alludes. This may be possible, because in her Selected Bibliography she references the actual catalogue of the Liman Collection from Marisa Kayyem and Paul Sternberger, Victorian Pleasures: Nineteenth-Century American Board and Table Games from the Liman Collection.

For Game Designers

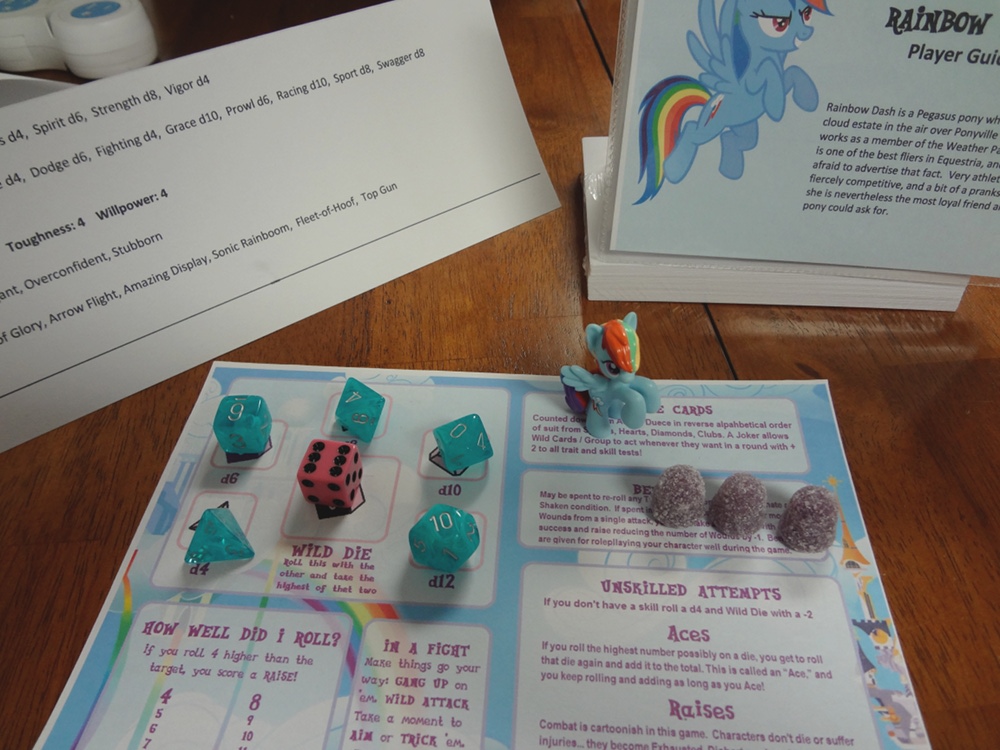

I think any game designer might enjoy at least thumbing through The Games We Played just for examples of past game mechanics that can be gleaned from studying the boards. Again, Hofer does not explain how each particular game was played. Also half of the illustrations at least are merely cover art. However for those more interested in the visual side of game design then, a perusal of Hofer’s book might be of value. Moving back to game mechanics, while a few games resemble Candyland such as Little Red Riding Hood and Jack the Giant Killer, Bulls and Bears: The Great Wall St. Game (a precursor to Monopoly) has a bit more to it. The Yacht Game Race and The Post Office Game both have New York as their setting and could be used to learn its geography, but a designer could extrapolate their game boards to fantasy and science fiction settings. Looking at the two boards for the New York games, I think something interesting could be done with a Minas Tirith or King’s Landing board game. Mystery at Hogwarts and Hogwarts: House Cup Challenge don’t begin to scratch the surface of what could be possible with a strong Hogwarts-based game.

In the Classroom

Lastly as a former long-term substitute teacher married to a teacher, I think The Games We Played has a place in a teacher’s library in any school setting. I see it as more of a topical temporary addition in an elementary school classroom with a teacher showing a few relevant pages to address a student’s question or accompany an area of study, though social studies is woefully inadequately taught at the elementary level. Older students will obviously get more out of the book. A middle school social studies teacher I once studied under was fond of using political cartoons to frame her students’ study of American history. Board games and their history could likewise frame a study of the post-Reconstruction period.

The only really questionable content in The Games We Played is on page 20 in the introduction with the cover of Jim Crow Ten Pins or possibly depictions of Native Americans. Of course, there is also the sexism of some of the games, but these are all approachable in their own right as topics of history handled by a veteran teacher. Most students however, encountering the picture of Jim Crow Ten Pins, will react to it and want to share it with their neighbors.

All images copyright Princeton Architecture Press, used with permission.