GAMA Trade Show Manufacturing Seminars

Larry Roznai of Mayfair Games: Domestic Manufacturing 101

I only caught the tail end of Larry Roznai providing advice to would-be manufacturers and game developers at the Domestic Manufacturing 101 seminar. Larry has a strong, confident personality and a very colorful vocabulary, so I can only imagine what I missed earlier and cannot post one of the more evocative expressions he used. He also loves working at Mayfair Games, where he is company president, and being surrounded by games and gamers, claiming happily, “this is nothing like a real job.”

One of the benefits of domestic manufacturing that Roznai covered when I arrived is the increased chance of getting credit from a printer. If a company can get 30 days credit, that is money that can be used elsewhere for those 30 days. It may require an extensive and intrusive credit check, but it can be worthwhile, according to Roznai. Credit terms are much harder to obtain with foreign companies.

Someone asked about cover art and where it fit into the schedule. Roznai affirmed that artwork is necessary for a distributor to solicit interest from retailers, but the entire game need not be finished. He advised that the artwork should be included in the cost of the first printing, as well as all of the tooling, and that these expenses not be amortized.

Then the question of Kickstarter came up and why Roznai thinks it may not be good for a manufacturer. To Roznai, making deals on Kickstarter is selling the cream of the crop. It can potentially exclude the retailer. Either Roznai or another attendee cited Darwyn Cooke, “You can piss off your customers, but you should never piss off your retailers.” Game manufacturers should want their audience of “1500 hardcore mother geeks” buying their game from retailers. Several attendees did not agree and voiced their differing opinions.

They also spoke up with their own experiences. Don’t go up against a Magic release, one warned. Another pointed out that releasing your game the week of Gen Con can actually kill it, because gamers are already spending their cash elsewhere that week. As for how often to contact a distributor about your game, Roznai said you “can’t go to a distributor often enough to pimp your game.”

Overseas Manufacturing

I and many other attendees crowded into the Overseas Manufacturing seminar, hosted by AEG and partner Panda Game Manufacturing.

John Zinser, AEG

John Zinser, President of Alderac Entertainment Group, shared his experiences with overseas manufacturing, which AEG has been doing for 4 years now. The initial move to overseas manufacturing surprisingly wasn’t motivated by domestic costs, it was actually a customer service issue for AEG. When the collectible card game industry collapsed, domestic printers started scrambling and the level of customer service AEG received dropped. As the makers of Legend of the 5 Rings, this was of major concern to Zinser and he has found that in China and Germany there is a higher level of customer service.

Another draw of overseas manufacturing is the difficulty in finding good plastics in the United States or at least Zinser hasn’t found them yet. This meshes with the fact that Reaper Miniatures has initially done its plastic Bones line overseas, even though they plan on bringing production in house.

Overseas manufacturing is about relationships, systems, and check-ups. If you’re manufacturing in China, Zinser says remember that:

- no deal is ever completely closed

- the wider the parameters, the more leeway the manufacturer will take

Even for domestic manufacturers, or those in Germany as well as China, Zinser advocates providing them with examples of other manufacturers’ quality. The manufacturers will in turn use the samples as their own benchmarks for quality.

When AEG started overseas manufacturing, they made many mistakes. They got back a “myriad” of things, some amazing to Zinser, and others from the exact same partners that made them “cringe”.

AEG Production Manager David Lepore

Zinser introduced Dave Lepore, head of production at AEG Games who began outlining his work process at AEG though Zinser occasionally contributed an explanation or made a few suggetions.

Lepore’s lengthy process begins when he talks to AEG’s game developers who already usually have a basic knowledge of the components they will want for the game. He begins to quote out the product to suppliers. If a developer initially comes with a game that has 100 cards and then wants 150 cards after revisions, it will probably necessitate a new quote.

To help in the process Lepore uses a preliminary specification sheet, listing whether tokens are wooden or plastic, what sort of punch card will be used, and so on. As the game moves on, he gets a list of final specifications. Next AEG prints up a protoype of the game in house, using the “fiddly bits” from other companies to test the production aspects of the game.

After the final specifications are complete, he then gets quotes from at least 3 suppliers if not more, including 1-2 domestic suppliers. He builds a spreadsheet to look at all the numbers and requests samples from the manufacturers of similar products, components and things like the plastic vacuum trays that organize most board games’ pieces. He gets very specific, what does Company X’s matte varnished punch board look like, what does your linen texture feel and look like? What about their matte texture? 280 gram cardstock versus 300 gram cardstock, Lepore requests it all.

When they arrive he labels the samples and begins to catalogue the advantages. A product might have great depth of print quality. That gets noted. The costs do as well. Sometimes costs are plainly divided as line item costs, while other companies return quotes with blanket costs. Obviously having line item costs gives Lepore more insight into how a change in the game could affect the cost. This process takes about 1-2 weeks. Any manufacturer taking much longer doesn’t want the business enough.

Lepore suggests soliciting the opinion of manufactuers who oftentimes will know about possible subsittutes or other ways of making a game from past experiences. On the other hand, no matter how impossible your need is, Chinese manufactuers have the attitude that “we are going to find a way to do it.”

Once the manufacturing company has been selected, the work doesn’t stop. Dave Lepore looks over an electronic proof of the game in house. He reviews barcords, SKUs, and legal text. It should have already been reviewed by the designers’ project leads who must insure that all 20 of their 20 cards are actually in the soft proof. Lepore then makes a digital proof, and again looks the game over. The digital proof is the last opportunity to get a feel for the color and feel of the game. Dave looks at color balance, graphic artififacts and remnants like little white lines unseen on the computer screen or boxes appearing in print that are not displayed on screen.

Having approved the digital proof, AEG sends the game to the manufacturer.

As soon as possible, they want the production sample, the first of the game to come off the line. According to Lepore, he has a “huge” checklist that he goes over to ensure the product is what it should be, including dropping the box from at least 2 feet up and checking to make sure that images and text aren’t reversed. The clearer you were about the quality and the more samples you provided to the manufacturer of what you expect, the better the result. As for what happens should the production sample be off, it depends on the terms you have set up with your manufacturer.

Michael Lee from Panda Game Manufacturing

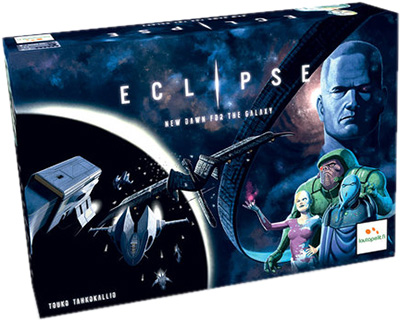

Fortunately there was an overseas manufacturer on hand who then covered his end of the business. Michael Lee from Panda Game Manufacturing in China was AEG’s guest at the GAMA Trade Show. The manufacturer of titles such as Pandemic and Eclipse as well as being a partner with AEG, Panda has been very busy over the last 18 months, especially with the Kickstarter craze.

Lee suggested that game developers keep things simple for their first game stating that “even experienced publishers make mistakes” when new to overseas game manufacturing. He advised that beginners choose one thing to tackle, two at most. Games combining multiple materials and technologies won’t make good first time overseas ventures. Plastics are particularly challenging.

Lee stressed the need for a very good graphic designer to avoid many common pitfalls he has seen, otherwise there are problems for those who don’t understand bleed or the need for CMYK colors. Lee cited Z-Man Games as a company with a very strong working relationship with Panda Manufacturing and strong knowledge of the process; Panda can get through the production process on a Z-Man game in 10 days.

He also warned new developers not to undersestimate their own pickyness when it comes to what they want from their game and how that can add time to manufacturing. In his experience, they can be very protective of their baby. On the other hand though, the manufacturers that they might be dealing with might not be board game manufacturers. I believe that Zinser and Lee both agreed that there are 4 to 6 good manufacturers to work with in China.

As for how long the process takes on his end, Lee said a good estimate is 4-5 months from FTPing your files until the product should arrive at the warehouse. First time designers should factor in a couple of extra weeks of buffer time. Shipping alone is usually 5 to 6 weeks. The prepress process usually takes a month on average, but it could take as long as 6 weeks or more. Lee reaffirmed that the average Euro takes 4-5 months. Once the production sample is ready, Panda FedEx’s to the client “and hopefully you’ll smile”. Sometimes, he said, the fault is with the manufacturers and they will work to correct it at their cost.

Shipping was the final topic that Lee and also Zinser spoke on. A large container is 40 feet, while a small is 20 feet. 5,000 Pandemic games fit into a small container. When shipping, it is best to:

- get one 40 foot container rather than two 20 foot containers

- fill your container or fill exactly half a container

- share your container with another American client if you are not filling it entirely to split shipping costs

Shipping costs vary depending on the season, but in March 2012, when they spoke, costs varied from $3,500-$4000 for a 40 foot conainer. That is the cost for the trans-Pacific freighting, but to actually go from the manufacturer to the receiving company’s warehouse door-to-door, could vary from $3000-$6500.

A Few More Thoughts on Manufacturing

Michael Lee has written his own overview of how board games are manufactured at PlayTMG. Speaking to several other attendees later about the manufacturing seminars, everyone consistently agreed on how much value they took away from them. Larry Ronzai held a second Domestic Manufacturing seminar later, which I did not attend, one of many other manufacturing seminars offered at the GTS including Demystifying QR Codes, How to Work Your Booth, and the mammoth New Manufacturer’s Orientation. Most gamers, myself included, have a few games or gaming products they want to develop. The GAMA Trade Show does seem to be the place to go for starting your game company. I should also point out how friendly and welcoming GAMA members are to their future competitors. This was also the case at the retail seminars. The focus is on growing the hobby and industry and providing better games.

Pingback:GAMA Trade Show Crowdfunding: Kickstarter and Indiegogo | Craven Games: In-Depth Tabletop Games Coverage

Pingback:The 2012 GAMA Trade Show: What Went On and Who Did It | Craven Games: In-Depth Tabletop Games Coverage